The Benefit-Risk Ratio and its Significance for the Clinical Evaluation of Medical Devices

01/07/2024

Do you have any questions about the article or would you like to find out more about our services? We look forward to hearing from you!Make a non-binding enquiry now

Clinical Evaluation of a medical device is all about benefit-risk assessment. The Medical Device Regulation (EU) 2017/745 (MDR) specifies the purpose and requirements for clinical evaluation, such as demonstrating conformity of a device with the relevant general safety and performance requirements, specifying the level of clinical evidence required, what the clinical evaluation plan should look like, etc. But what it all boils down to is assessing the benefit-risk ratio of a device and the acceptability of that ratio.This may sound straightforward at first, but as anyone involved in clinical evaluation reporting will know, it can become tricky when you get into the details, such as: What is the benefit to whom and under what conditions? What risks should be considered? And finally, how should I balance the two? And what (the heck) does acceptable mean?In the following, we hope to bring some clarity to these issues.

"[…] that any risks which may be associated with their use constitute acceptable risks when weighed against the benefits[…]" and in GSPR 3c requests manufacturers to "estimate and evaluate the risks associated with, and occurring during, the intended use and during reasonably foreseeable misuse".Further, a Position Paper by The European Association of Medical devices Notified Bodies (Team-NB) (NB Position Paper on "Data generated from "Off-Label" Use of a device under the EU Medical Device Regulation 2017/745") states the expectation of Notified Bodies that data from off-label use, when identified, "should always be considered as part of the clinical evaluation of a device […] to reduce or eliminate the risks of future misuse."Comment: Unfortunately, as the MDR does not define "off-label use" or "misuse", though it uses both terms in Annex XIV Part B, neither does the position paper always clearly distinguish between the two terms.Our conclusion is that the benefit-risk assessment of the clinical evaluation generally refers to the intended use of the device(s) under evaluation. However, the clinical evaluation should also address off-label use. On the one hand, to assess its risks, but on the other hand, particularly in the case of systematic off-label use, also to determine whether there is a need in the medical community for such a new use.

"[…] against the evaluated benefits to the patient and/or user".The definitions of clinical benefits for the patient are easy to understand and are, of course, included in the clinical evaluation.As for the benefits to users, these can be typically related to one of the following three categories:Economic benefits in their purest form are not relevant to clinical evaluation. Therefore, they should only be considered if they have an impact on the patient. For example, lower overall treatment costs may make therapy more accessible to certain patient groups. Or shorter treatment times might be an economic benefit for the user, while at the same time reducing the risk of infection for the patient in case surgery is involved.Increased convenience usually means an improved usability, which in general has the added benefit for the patient of reducing the potential for user error.Less impact on the user's health usually means that the user is less likely to experience negative effects on his/her own health. A negative impact on the user's health would be a harm and therefore more likely to fall under the safety discussion, which clearly includes impacts on the user anyway (see below).In summary, user benefits relevant to the clinical evaluation may often include benefits to the patient. We typically address these patient aspects of user benefits in the clinical evaluation to meet the different requirements of the MDR.

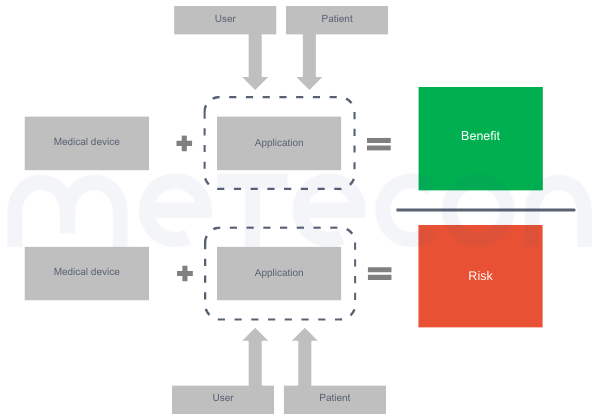

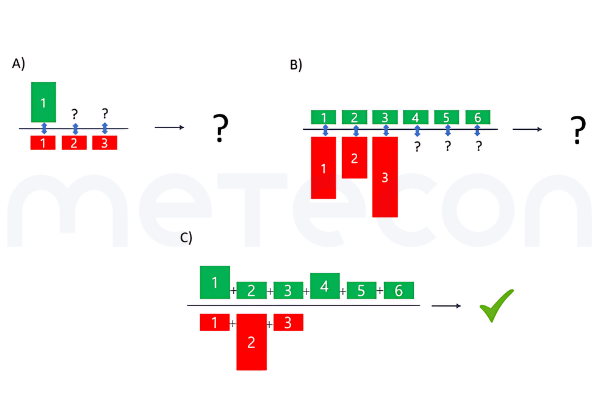

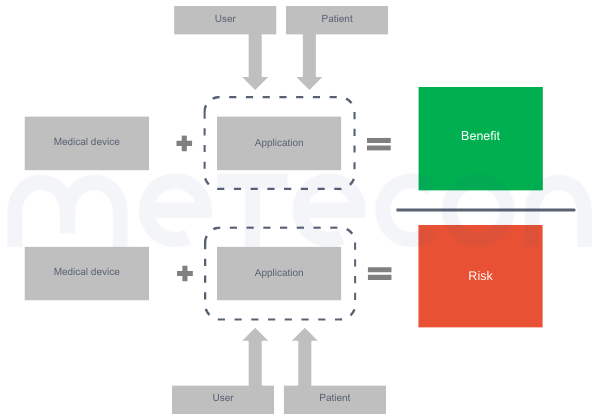

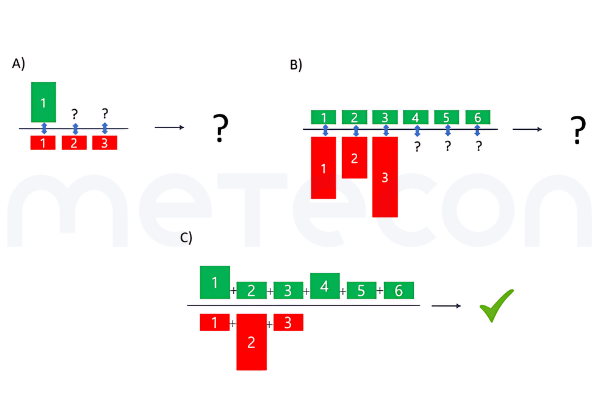

Figure 1: Factors to be considered in benefit-risk assessmentThe main question faced by clinical evaluators is usually: but how to compare? The first problem is that such an evaluation is likely to be highly individualized. For example, some benefits may be more important to one population (e.g. the aesthetic outcome of dental treatment for an actor or model) than to another. The same applies to risks, since different people have different needs for safety. Therefore, we need to make simplifications and provide an estimate for an "average patient".In addition, the MDR requests that we consider the generally acknowledged State of the Art (SotA) when determining the acceptability of risks when weighed against benefits (e.g. in GSPR 1). While the MDR also lacks a definition of "State of the Art", MDCG 2020-1 and MDCG 2020-6 refer to the definition of the International Medical Device Regulators Forum''s Good Regulatory Review Practices Group (IMDRF/GRRP) in their guidance on "Essential Principles of Safety and Performance of Medical Devices and IVD Medical Devices" (WG/N47) and define "state of the art" as"Developed stage of current technical capability and/or accepted clinical practice in regard to products, processes and patient management, based on the relevant consolidated findings of science, technology and experience.Note: The state-of-the-art embodies what is currently and generally accepted as good practice in technology and medicine. The state-of-the-art does not necessarily imply the most technologically advanced solution. The state-of- the-art described here is sometimes referred to as the "generally acknowledged state-of-the-art" (source: modified from IMDRF/GRRP WG/N47 Final:2018)."Therefore, considering the state of the art does not mean comparing your device to the most advanced treatment or technology, but rather to what the patient could expect to receive with standard care.Another issue may be how to weigh the benefits against the risks for this average patient. As discussed above, there is usually more than one benefit and certainly more than one risk. So the question is what to compare with what. It is usually not possible to directly weigh one benefit against one risk because the risks and benefits vary in magnitude and number (see Figure2 A) and B)). Therefore, the total sum of the benefits should be compared to the total sum of the risks (see Figure 2 C)).

Figure 2: Comparisons of benefits and risks. A) Direct comparison of one benefit to one risk out of several, with all risks having the same extent B) Direct comparison of different benefits of the same extent to different risks of varying extent and unequal numbers compared to the benefits C) Comparison of a total benefit to a total riskEasier said than done? Here is an overview of how to approach such a comparison.

Scope of evaluation: Intended purpose vs. off-label use

The conditions of use to be considered in the clinical evaluation are defined in Article 2 (Definitions) of the MDR where point 44 defines clinical evaluation as a process meant to "assess the clinical data pertaining to a device in order to verify the safety and performance, including clinical benefits, of the device when used as intended by the manufacturer;" and point 24 defines benefit-risk determination as "the analysis of all assessments of benefit and risk of possible relevance for the use of the device for the intended purpose, when used in accordance with the intended purpose given by the manufacturer".Please note: Emphases on certain phrases in these and the following quotes from regulations have been added by the authorHowever, other parts of the MDR request a broader analysis, particularly of the risks, as in the General Safety and Performance Requirements (GSPRs) in Annex I, Chapter I of the MDR which demands in GSPR 1.Relevant benefits to consider

Benefits to whom?

The MDR in Chapter 1 Article 2 point 53 defines clinical benefit as "the positive impact of a device on the health of an individual, expressed in terms of a meaningful, measurable, patient-relevant clinical outcome(s) related to diagnosis, or a positive impact on patient management or public health". So while the definition of clinical benefit clearly emphasises the outcome for the patient, that is not the only point of focus of the MDR, as GSPR 8 goes on to clearly weigh risks and side-effectsWhat benefits?

The benefit results from the use of the medical device, which may include a specific procedure such as surgery. The overall procedure and its outcomes, i.e. the resulting benefit, may be influenced by the user and/or the patient.Eventually, there will be an evaluation of risks versus benefits in the clinical evaluation. And since we need to consider all the risks in this evaluation (see below), we should also consider all the benefits of the device(s) under evaluation. This may sound straightforward. However, in practice we sometimes find that manufacturers focus on one benefit only and neglect others in their technical documentation.Relevant risks to consider

Risks for whom?

The persons to be considered in the safety analysis are, thankfully, more clearly defined by the MDR than is the case for the benefits. For example, GSPR 1 states: "They […] shall not compromise the clinical condition or the safety of patients, or the safety and health of users or, where applicable, other persons, provided that any risks which may be associated with their use constitute acceptable risks when weighed against the benefits to the patient and are compatible with a high level of protection of health and safety […]".In short: any risk to any person must be considered.What risks?

As discussed above, all risks must be considered. This means device-specific risks, i.e. risks directly related to the device itself (such as fracture of an implant, or allergic reaction to materials incorporated in the device), but also risks associated with the procedure required to deploy/apply the medical device (such as bleeding or tissue injury in the case of a surgical procedure). As with the benefits, procedure-related risks can be influenced by users and patients.This also means that the clinical evaluation may consider more risks than the risk management file, which has a focus on risks associated with the use of the medical device, i.e. device-related risks.How to weigh benefits and risks

Once all the benefits and risks have been identified, the clinical evaluation needs to discuss the resulting benefit-risk ratio:

Figure 1: Factors to be considered in benefit-risk assessmentThe main question faced by clinical evaluators is usually: but how to compare? The first problem is that such an evaluation is likely to be highly individualized. For example, some benefits may be more important to one population (e.g. the aesthetic outcome of dental treatment for an actor or model) than to another. The same applies to risks, since different people have different needs for safety. Therefore, we need to make simplifications and provide an estimate for an "average patient".In addition, the MDR requests that we consider the generally acknowledged State of the Art (SotA) when determining the acceptability of risks when weighed against benefits (e.g. in GSPR 1). While the MDR also lacks a definition of "State of the Art", MDCG 2020-1 and MDCG 2020-6 refer to the definition of the International Medical Device Regulators Forum''s Good Regulatory Review Practices Group (IMDRF/GRRP) in their guidance on "Essential Principles of Safety and Performance of Medical Devices and IVD Medical Devices" (WG/N47) and define "state of the art" as"Developed stage of current technical capability and/or accepted clinical practice in regard to products, processes and patient management, based on the relevant consolidated findings of science, technology and experience.Note: The state-of-the-art embodies what is currently and generally accepted as good practice in technology and medicine. The state-of-the-art does not necessarily imply the most technologically advanced solution. The state-of- the-art described here is sometimes referred to as the "generally acknowledged state-of-the-art" (source: modified from IMDRF/GRRP WG/N47 Final:2018)."Therefore, considering the state of the art does not mean comparing your device to the most advanced treatment or technology, but rather to what the patient could expect to receive with standard care.Another issue may be how to weigh the benefits against the risks for this average patient. As discussed above, there is usually more than one benefit and certainly more than one risk. So the question is what to compare with what. It is usually not possible to directly weigh one benefit against one risk because the risks and benefits vary in magnitude and number (see Figure

Figure 2: Comparisons of benefits and risks. A) Direct comparison of one benefit to one risk out of several, with all risks having the same extent B) Direct comparison of different benefits of the same extent to different risks of varying extent and unequal numbers compared to the benefits C) Comparison of a total benefit to a total riskEasier said than done? Here is an overview of how to approach such a comparison.

Routinely used devices

In case you have a medical device that belongs to a fairly established and widely used group of devices, it can be assumed that the benefit-risk ratio of this device group is known and generally accepted by the medical community and by patients, including when alternative treatments are considered. Otherwise, it would not be used routinely. Therefore, in this case, we assume that it is sufficient to demonstrate that the device under evaluation has similar or superior benefits and similar or lower risks than the devices in the same device group which are usually used as benchmarks. When this is demonstrated, it can be argued that the benefit-risk ratio of the device under evaluation is acceptable. Of course, the alternative treatments still need to be described, with their advantages and disadvantages, but at a rather low level of detail.However, there may be exceptions from this rule, particularly when the state of the art is evolving, and the market/clinical use has a lag time to adapt to the new device types or treatments. This must of course be taken into account for the specific device(s) under evaluation.Not routinely used devices

For more innovative devices or niche products, the approach mentioned above is not applicable and a specific benefit-risk comparison needs to be made for the device under evaluation. But how can this be done?Harms are already weighted in the risk analysis according to their severity and frequency. For the benefit-risk assessment, it may be helpful to apply a similar weighting to the benefits in order to compare them with the risks. For instance, if the benefit is live saving, life-threatening risks might be acceptable. Conversely, if the benefit is only increased comfort, a severe health risk is unlikely to be acceptable. Although these are extreme examples, some weighting of benefits against risks can provide a solid basis for your benefit-risk discussion. However, we strongly discourage a full mathematical calculation of the benefit-risk ratio, as (a) this can be rather complex, impossible with the available data, or oversimplified and therefore misleading, and (b) is not required by MDR or associated guidance documents.Final remarks

As we have discussed, the clinical evaluation is ultimately a benefit-risk evaluation. Although some definitions and requirements are not explicitly or uniformly described in the MDR, we can approach this evaluation with common sense. We can ask ourselves what we would like to know and consider if we had to make a decision for or against a certain treatment for ourselves or for our loved ones as patients. Most likely, this approach will enable you as the manufacturer to write a stringent story about your benefit-risk evaluation, which will also convince the Notified Body.If you have any specific questions regarding your own product(s) or could use a helping hand, we are here to help you find an efficient approach to your benefit-risk assessment and clinical evaluation. Feel free to email the author directly or use our contact form to reach us.

Our blog posts are researched and created with the utmost care, but are only snapshots of the regulations, which are constantly changing. We do not guarantee that older content is still current or meaningful. If you are not sure whether the article you have read on this page still corresponds to the current state of regulation, please contact us: we will quickly place your topic in the current context.