Validation of software for quality management and manufacturing - risk-based, efficient, and compliant

25/08/2025

Do you have any questions about the article or would you like to find out more about our services? We look forward to hearing from you!Make a non-binding enquiry now

Software is taking on more and more tasks in medical technology. But how do manufacturers ensure they are on solid regulatory ground? Whether document management, process monitoring, or traceability: software used in the quality management system (QMS) or in the manufacture of medical devices is subject to strict requirements. ISO 13485 and the FDA require validation, but what does that mean in practice? When is a pragmatic solution sufficient, and when is depth required? In this article, we examine the requirements for validating software in the context of QMS, highlight typical challenges, and offer ideas for how a risk-based approach can reconcile effort and compliance.

The FDA also specifies concrete requirements in 21 CFR 820.70(i) under Production and Process Controls. It is made clear that software that is part of production or the QMS must be validated, and a documented procedure for doing so is required.Other documents relevant to software validation in the context of medical device QMS, in addition to ISO 1345 and 21 CFR 820.70, include:

The core idea is the same throughout: the scope and depth of validation must be aligned with the risk that faulty software functions could pose to patient safety or regulatory compliance.Note: It is essential to distinguish whether you are dealing with validation of software for a medical device or validation of software used in the QMS context. Different regulatory requirements apply in each case.

If the answer to either question is "yes," the software must be validated.The software's intended use is the primary argument if you conclude that validation is not required. It is therefore always advisable to document such decisions so the rationale is readily available. Depending on the software’s complexity, a more detailed assessment with a risk analysis may be needed to determine which functions require validation.

Only software that is part of the QMS or production needs to be considered. This explicitly excludes, for example, accounting software, HR management software, or email applications.

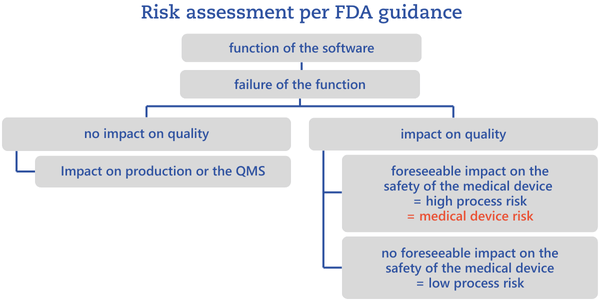

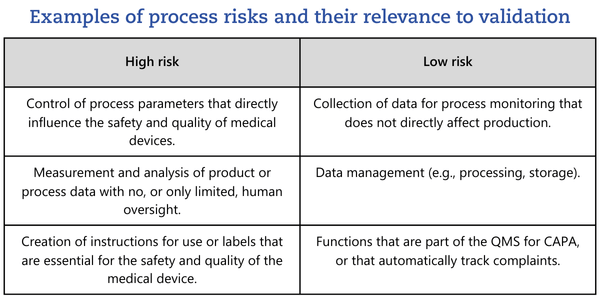

Depending on the level of risk, choose validation methods accordingly: simple reviews for low risk, and structured test procedures for high risk. The FDA additionally distinguishes between process risks and medical device risks. A high process risk exists when failure of a function would impair quality in a way that would predictably affect the safety and performance of the medical device.

In other words, a high process risk is a risk that can ultimately give rise to a medical device risk.

This high/low split is not mandated by the FDA guidance. Categories should be chosen sensibly, always considering whether further granularity would add value.To perform the risk analysis described, it is essential to clearly define the process in which the software is used.

The intensity of testing in software validation should always be proportionate to the risk arising from potential malfunctions. For high process risk, the yardstick is the potential risk to the medical device. If process risk is low, a correspondingly reduced test strategy is sufficient.Important: This section addresses only software used in production or in the QMS - not software used in, or that itself constitutes, a medical device.The FDA recommends various test methods in its guidance, in particular:

Unscripted testing does not relieve you of the obligation to document both the test results and the approach taken.The higher the software risk, the greater both the testing effort and the density of evidence should be. Scripted testing provides the highest level of traceability and structure.Software should never be viewed in isolation. If the process includes additional controls that would detect errors, the validation effort can be reduced. The same applies to purchased software that has already been assessed or validated—your own testing activities can be adjusted accordingly.As always, a clear, traceable documentation trail is the key so that you can justify your approach in an audit. Ultimately, the manufacturer is responsible for determining which testing activities are appropriate for which risks.

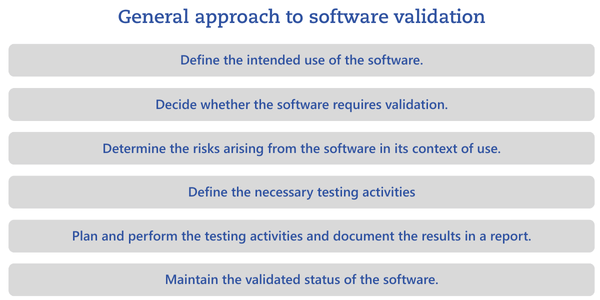

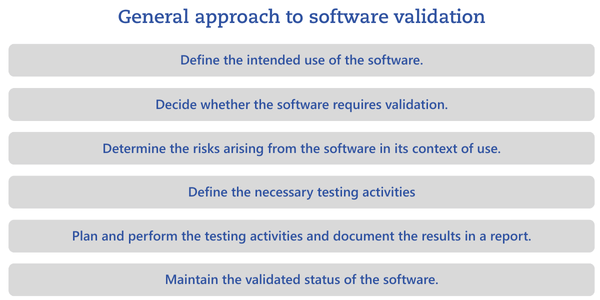

Regardless of the testing approach, malfunctions must be clearly documented and described. The test report should include a concluding statement as to whether the software is suitable for its intended use.The following chart shows a general approach to software validation and the steps that must be planned and documented.

Use case integrated software in manufacturing equipment: If software is used as part of equipment (e.g., a production line controller), validation can be performed via equipment qualification or process validation. ISO/TR 80002-2 recommends linking to that evidence or incorporating it directly into the software validation documentation.

Leon Weißenhorn

Leon Weißenhorn

Regulatory foundations: ISO 13485, 21 CFR 820, and FDA guidance at a glance

Software validation in medical technology is not a "nice to have" - it is mandatory under certain conditions.As digitalization advances, tasks and processes are increasingly performed by software, including in the manufacture of medical devices. Software used in this environment falls under the manufacturer's quality management system (QMS). The goal of software validation is to provide objective evidence that the software is suitable for its intended use and meets regulatory requirements.In several clauses (including 4.1.6, 7.5.6, 7.6), ISO 13485:2016 requires a documented procedure for validating computer software used in the QMS. The FDA likewise requires in 21 CFR 820.70(i) that software be validated prior to initial use and after changes: risk-based and thoroughly documented. Manufacturers are therefore tasked with validating software that is not part of the medical device itself.What sounds straightforward often creates significant uncertainty in practice: Which software is in scope? What exactly must be validated? How should legacy software or cross-system functions be handled?From the requirements of ISO 13485, the following activities result:- A documented procedure for software validation shall be established.

- Software applications that require validation, and those that do not, must be defined.

- Prior to initial use, the documented software validation procedure must be applied. If application prior to initial use is no longer possible, a retrospective assessment must determine whether validation is necessary, and, if so, to what extent.

- Changes to the software, or use for a different purpose, must trigger reapplication of the validation procedure (revalidation), as appropriate.

- Implementation of the procedure must be risk-based and consider the software’s context of use.

The FDA also specifies concrete requirements in 21 CFR 820.70(i) under Production and Process Controls. It is made clear that software that is part of production or the QMS must be validated, and a documented procedure for doing so is required.Other documents relevant to software validation in the context of medical device QMS, in addition to ISO 1345 and 21 CFR 820.70, include:

- ISO/TR 80002-2:2017 "Validation of software for medical device quality systems"

- FDA Guidance "General Principles of Software Validation" (2002)

- FDA Draft Guidance "Computer Software Assurance for Production and Quality System Software" (2022)

The core idea is the same throughout: the scope and depth of validation must be aligned with the risk that faulty software functions could pose to patient safety or regulatory compliance.Note: It is essential to distinguish whether you are dealing with validation of software for a medical device or validation of software used in the QMS context. Different regulatory requirements apply in each case.

When must software be validated?

21 CFR 820 and ISO 13485 are aligned on this point: software or software functions that are part of production or the QMS must be validated.To be more specific, ISO/TR 80002-2 defines the following questions in Clause 5.2.2:- Could failure of the software, or a software error, adversely affect the safety or quality of medical devices?

- Does the software automate or perform an activity that is required by regulation (particularly medical device quality management system regulations)? Examples include capturing electronic signatures and/or records, maintaining product traceability, executing and recording test results, and maintaining data logs such as CAPA, nonconformances, complaints, or calibrations.

If the answer to either question is "yes," the software must be validated.The software's intended use is the primary argument if you conclude that validation is not required. It is therefore always advisable to document such decisions so the rationale is readily available. Depending on the software’s complexity, a more detailed assessment with a risk analysis may be needed to determine which functions require validation.

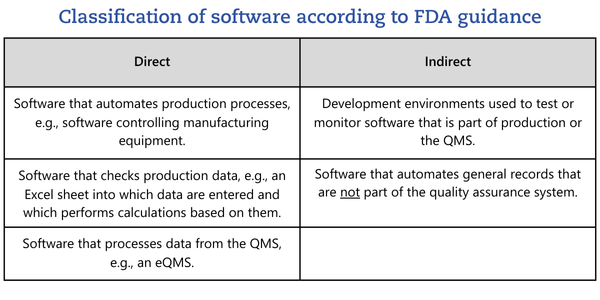

Direct, indirect, not relevant: classifying software in the validation context

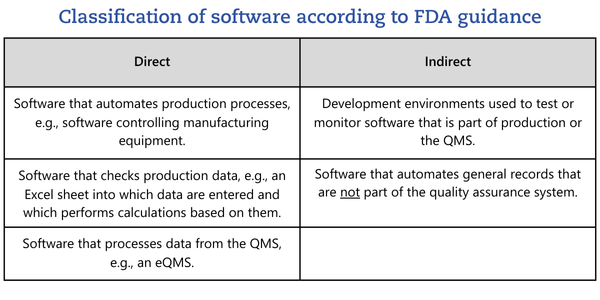

The FDA guidance proposes categorizing software as a direct or indirect part of production or the QMS:

Only software that is part of the QMS or production needs to be considered. This explicitly excludes, for example, accounting software, HR management software, or email applications.

Example: climate control and whether it must be validated

Whether software must be validated depends, as described, on the context of use. A common example is climate control software. If it is used only to regulate office temperature, it has no impact on product safety: validation is not required. It is different if the same software monitors and controls climate conditions in production rooms; in that case, a malfunction could affect product quality.Takeaway: Identical software can be assessed differently depending on the area of use; however, the decision should always be documented.Risk analysis and validation strategy: how much validation is appropriate?

Once you have determined that software must be validated, you need to determine which activities are required, i.e. what objective evidence must be generated for the software to be considered validated.You must identify potential failures, the risks those failures could create, and the activities needed to prevent them. This should be performed as part of a risk analysis. ISO/TR 80002-2, Clause 5.3.2.3, calls for a risk-based consideration across three categories:- Risks related to direct and indirect harm to persons (patients and users),

- Risks related to harm to the (physical and virtual) environment,

- Risks related to noncompliance with regulatory requirements.

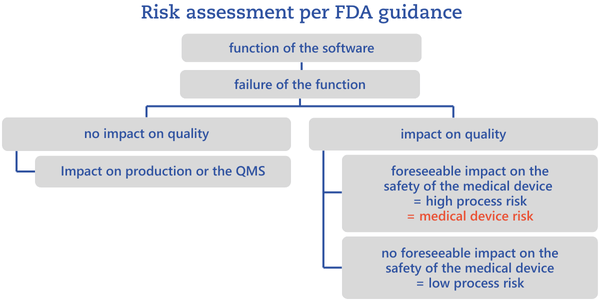

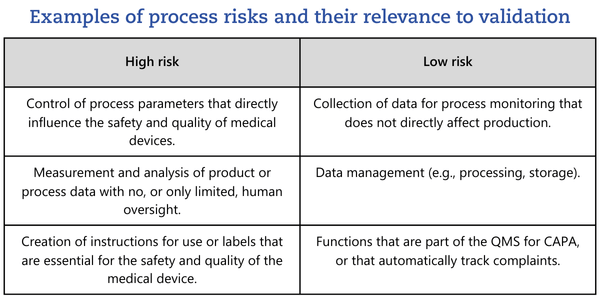

Depending on the level of risk, choose validation methods accordingly: simple reviews for low risk, and structured test procedures for high risk. The FDA additionally distinguishes between process risks and medical device risks. A high process risk exists when failure of a function would impair quality in a way that would predictably affect the safety and performance of the medical device.

In other words, a high process risk is a risk that can ultimately give rise to a medical device risk.

This high/low split is not mandated by the FDA guidance. Categories should be chosen sensibly, always considering whether further granularity would add value.To perform the risk analysis described, it is essential to clearly define the process in which the software is used.

Defining the necessary test activities

The intensity of testing in software validation should always be proportionate to the risk arising from potential malfunctions. For high process risk, the yardstick is the potential risk to the medical device. If process risk is low, a correspondingly reduced test strategy is sufficient.Important: This section addresses only software used in production or in the QMS - not software used in, or that itself constitutes, a medical device.The FDA recommends various test methods in its guidance, in particular:

- Scripted testing: predefined test cases and sequences,

- Unscripted testing: flexible, risk-based testing without a fixed script.

Unscripted testing does not relieve you of the obligation to document both the test results and the approach taken.The higher the software risk, the greater both the testing effort and the density of evidence should be. Scripted testing provides the highest level of traceability and structure.Software should never be viewed in isolation. If the process includes additional controls that would detect errors, the validation effort can be reduced. The same applies to purchased software that has already been assessed or validated—your own testing activities can be adjusted accordingly.As always, a clear, traceable documentation trail is the key so that you can justify your approach in an audit. Ultimately, the manufacturer is responsible for determining which testing activities are appropriate for which risks.

Documenting software validation efficiently: requirements for evidence, risk, and test scope

Documentation must provide objective evidence that the software or software functions fulfill the intended use. That intended use is the basis for all subsequent validation steps.The documentation should include:- A description of the software’s context of use and intended use,

- A risk assessment of the software,

- A description of the planned or executed testing activities,

- And, depending on the test method (scripted or unscripted), a detailed or high-level test plan, including acceptance criteria.

Regardless of the testing approach, malfunctions must be clearly documented and described. The test report should include a concluding statement as to whether the software is suitable for its intended use.The following chart shows a general approach to software validation and the steps that must be planned and documented.

Use case integrated software in manufacturing equipment: If software is used as part of equipment (e.g., a production line controller), validation can be performed via equipment qualification or process validation. ISO/TR 80002-2 recommends linking to that evidence or incorporating it directly into the software validation documentation.

Retrospective validation: what if software is already in use?

In established companies, software is often in use for years before software validation topics are addressed in a structured way. In such cases, retrospective validation is required, i.e. a subsequent assessment including risk analysis and documentation.Why software changes require continuous attention

The work does not end when software is introduced. Each new version may add functions or modify existing features. Such changes can introduce new risks that must be identified, analyzed, and evaluated.To make that possible, those responsible for software validation must always know the current state of the software configuration: continuously and reliably. This applies to all software solutions used in the QMS or in production.To ensure this transparency, you need a functioning system within your organization. This may be a structured process landscape supported by suitable tools, possibly even by a dedicated (and of course validated) software solution.Compliant, efficient, and audit-ready - not without a structured approach

Software validation is a key element of regulatory conformity under ISO 13485 and the FDA requirements. Particularly challenging are the retrospective validation of existing systems and the assessment of software functions at the boundary between QMS, production, and general IT applications.To balance validation effort and compliance pressure, a risk-based approach is crucial—ideally supported by experienced partners who combine technical depth with regulatory know-how.Are you facing the challenge of back-documenting older systems, or validating new software solutions efficiently and in conformity with regulations? We support you in analyzing, planning, and implementing tailored software validation processes—retrospectively, in parallel with digitalization, or as part of an internal audit.Contact us for a no-obligation initial consultation.

Our blog posts are researched and created with the utmost care, but are only snapshots of the regulations, which are constantly changing. We do not guarantee that older content is still current or meaningful. If you are not sure whether the article you have read on this page still corresponds to the current state of regulation, please contact us: we will quickly place your topic in the current context.

Regulatory Affairs & Technical Documentation